The latest issue of The Abolitionist paper is out! Subscribe today to get your copy, and support people in prisons, jails, and detention centers getting it for free.

Issue 29 of The Abolitionist takes Critical Resistance’s latest video project, Breaking Down the Prison Industrial Complex, and puts it into print. The goals of the video project are to 1) revisit a critical, grounded understanding of how the PIC operates today and why PIC abolition is essential, 2) highlight what shifts in common sense PIC abolition requires and ways that PIC abolition is being put into practical action, and 3) deepen current conversations about PIC abolition and to expand them by engaging new voices and audiences. We’ve chosen videos that encompass these goals to include in this issue of the paper, as sharing materials, analysis, and tools that we have access to outside of prison walls with people on the inside is crucial to building stronger abolitionist movement. Here’s a snippet from the Letter from the Editors:

Political education is key for developing a cohesive strategy for PIC abolition, both inside and outside prison walls…Because The Abolitionist is one of the primary strategies that we use to communicate with people inside prisons and jails, we felt that it was important to share portions of “Breaking Down the Prison Industrial Complex” with our readers inside through this vehicle. The PIC intentionally stifles the ability of imprisoned people to receive and share information in a number of ways, including banning or censoring formats such as video or audio recordings. Sharing transcripts is our way of resisting one way in which the PIC and its actors seek to exert power and control.

Check out the content of this issue:

- What’s Wrong with Community Control of Police? by Kamau Walton

- Learning Together How to Fight by Mariame Kaba

- Political Education and Resistance Inside by Masai Ehehosi

- When the Prison Industrial Complex Masquerades as Social Welfare by Ruth Wilson Gilmore (click here or scroll down to read!)

- Snuffing Out Human Potential by Claude Marks

- The Impacts of the Prison Industrial Complex by Laura Whitehorn

- What is the Prison Industrial Complex? by Mary Hooks

- Abolishing the Prison Industrial Complex by Marbre Stahly-Butts

- Fear of Analysis by Craig Gilmore

- It’s Not Police Brutality by Dylan Rodriguez

- A Community Context for Fighting the Prison Industrial Complex by Jose E. Lopez

- Abolition is Our Obligation by Dylan Rodriguez

- A Response to Lee Correctional Facility Tragedy, shared on behalf of Jail House Lawyers Speak

- Introducing: Care Not Cages Zine by Decarcerate Alameda County and Prison Renaissance

- Review of: ABO Comix Queer Anthology #1 by Woods Ervin

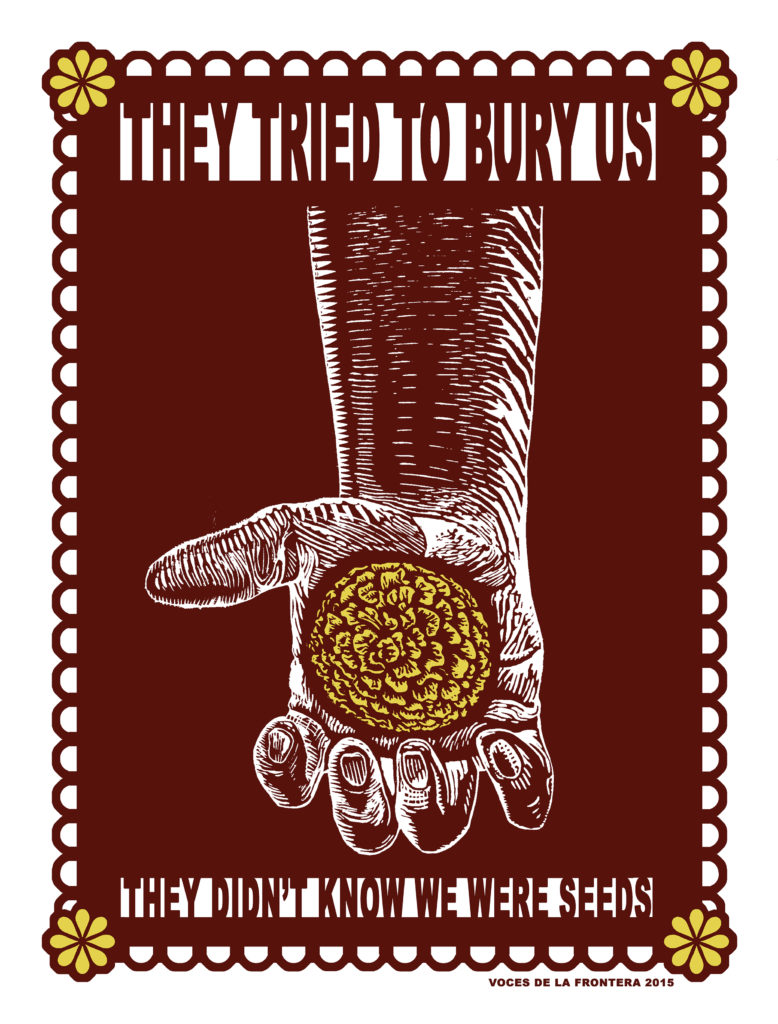

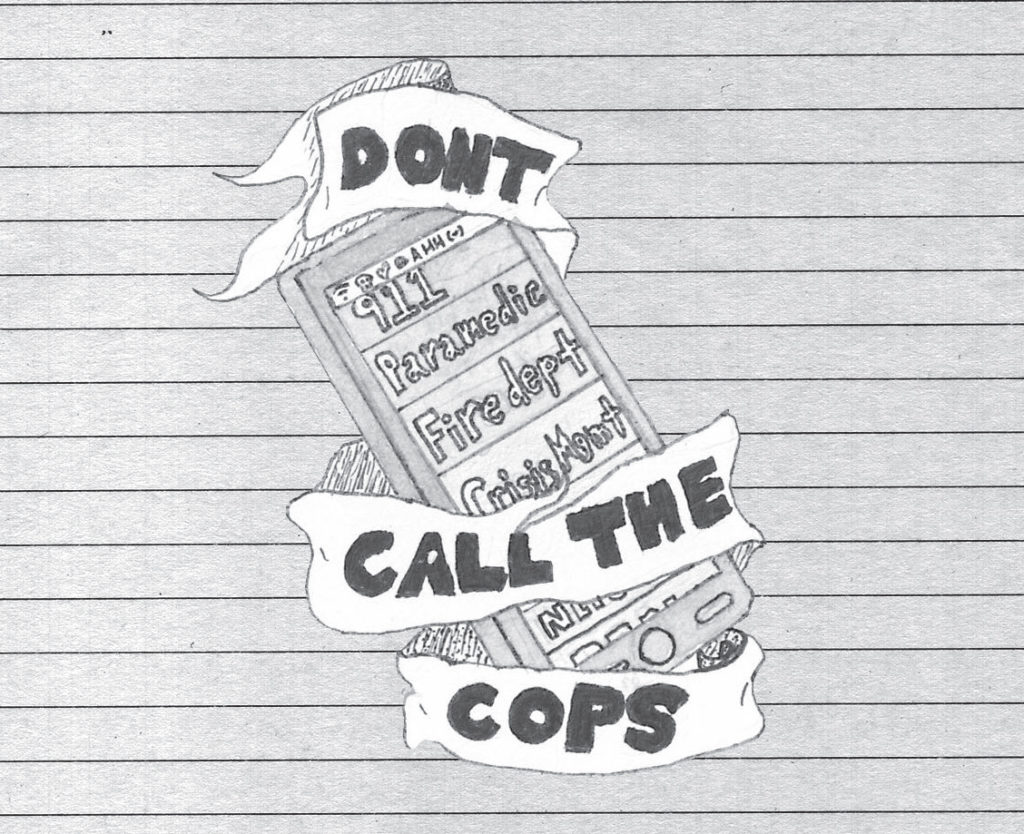

Art in this issue

.

When the Prison Industrial Complex Masquerades as Social Welfare

By Ruth Wilson Gilmore

Underlying the prison industrial complex there’s been a consistency—to target vulnerable people. The definition of vulnerable has some variation over time and space, and we can see greater intensities in certain times and places, and lesser in others. So, for example, modestly educated people in the prime of life, who are not white have been targeted significantly. But so have white people, especially, but not exclusively, in rural America. People not documented to work have been targeted. But so have people who have been documented not to work—which is to say people who have been carrying convictions, regardless of their citizenship status.

But what’s also key to my understanding of what’s going on now, is the fact that police departments—what they like to call themselves—police organizations, over time, have gotten greater and greater power to participate in many aspects of social life that other state agencies used to take care of. In other words, police organizations—especially in big cities here in New York City, in the city of Los Angeles, and we could probably name many, many others—have internalized the mission of social welfare organizations. And the difference between what they do, and what these other state agencies do, or have done, is that they demand a certain kind of self-policing or unmatched deputy status in order for people to qualify for meager social goods and benefits.

At the same time, agencies whose mission has never been about policing and punishment—let’s say the United States Department of Education, or, you know, any number of welfare and other agencies, health, for example—have internalized the mission of policing in order to allocate the scarce resources that they have between the so-called deserving and the undeserving. So, one case in point that I like to use as an example is the United States Department of Education has a SWAT team. Why would they have a SWAT team? To legitimize what they do in the eyes of the completely delegitimized, and yet still large, set of agencies whose work is supposed to be social welfare, social goods, social benefits, and, dare I say, social justice.