Interview by Dylan Brown of The Abolitionist

Editors’ Note: The following article is a transcript of a conversation between Dylan Brown of Critical Resistance’s The Abolitionist Editorial Collective and former anti-imperialist political prisoner, Susan Rosenberg. In 1986, Susan Rosenberg was one of the first women imprisoned in the High Security Unit at FCI Lexington, an experimental total lockdown isolation unit in the basement of a building, totally separate from the rest of FCI Lexington. The Lexington Control Unit was designed for the express purpose of caging women political prisoners involved in revolutionary struggles. This interview has been edited for length, order, and clarity, and was conducted for the Fall 2023 / Winter 2024 issue of Critical Resistance’s The Abolitionist newspaper, Issue 40 on control units. To support free subscriptions of the newspaper for imprisoned people, and to receive your own copy of the complete issue, subscribe today!

Brown: Can you speak to the political conditions that led to the creation of the Lexington High Security Unit (HSU) in 1986, and the significance of this unit in the effort to contain and control women involved in revolutionary struggles?

Rosenberg: From the late 1960s and into the early 1980s, revolutionary activity was going on against the US, and there was repression through COINTELPRO that was “officially over” in the late 1970’s – but not really. During this period, a number of our movement leaders were imprisoned at similar times. They were Puerto Rican independentista revolutionaries, Black revolutionaries, New Afrikan freedom fighter revolutionaries, and anti-imperialist political prisoners. There were more women at that moment part of revolutionary movements who were caught, tried, and imprisoned—of which I was one.

In the 1970s, the “war on drugs” began as rhetoric that turned to a literal war against Black, Puerto Rican, and poor communities, instigating a whole generation of people going to prison in the 1970s and 1980s. The US government was building more repressive apparatuses—high security prisons—for the current wave of revolutionary political activism against the US and for what would come in the future. For example, the Reagan administration imported and exported isolation as a mechanism of imprisonment. Political prisoners in Germany,Uruguay, Spain and Ireland were the first wave of people imprisoned under these torture-like conditions utilizing isolation as the mechanism to drive people either insane or to die by suicide. While solitary confinement and torture existed already, it hadn’t existed at this scale, and in such a systematic targeted way.

There were a number of factors that went into creating the conditions for these units. The first lock-down prisons were in the federal prison system—the Marion prison was one of the very early prisons in complete lockdown, which meant everybody in that prison was in solitary confinement and in units that existed for that purpose. Before Marion and Lexington, there was an experimental isolation wing at FPC Alderson in West Virginia where Assata Shakur, Marilyn Buck, Susan Saxe, Saffiyah Bukari and Lolita Lebrón were all imprisoned temporarily, in isolation. That was one of the very first attempts to destroy women involved in radical and revolutionary political and literal activity.

Brown: How have you seen the prison industrial complex (PIC) shift and evolve since the closure of Lexington HSU? What strategies and tactics have you seen emerge?

Rosenberg: Well, I think Lexington HSU was an experiment by the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) and the FBI. The point of that unit was to break us, to have us renounce our political beliefs, to “go crazy”, to isolate us, and to try and break the movement’s support of us and our relationship to the movement. That was really the intention. And while we won litigation against Lexington HSU and got the unit closed, it was overturned on appeal. Up until Marion and Lexington, you were sentenced to prison, and if people went into solitary confinement it was a punishment for behavior that occurred while you were in the prison itself. Once our case got reversed on appeal, it meant that the BOP could put any prisoner in any prison in any location for any length of time without any due process or external accountability around that. This gave them the green light to build these units in multiple places, which they did over the rest of the 1980s and the 1990s. It was also the period where the rise in the actual population of people in prison grew exponentially. These numbers remained on the rise—with the war on crime, the war on drugs, and then the war on terror, which came a little later.

While we won something and were able to ex- pose some of the terrible treatment that we (political prisoners) were getting, we always took the position that if they can do it to us, then they can massify it and do it to everybody. The PIC emerged out of the desire to incapacitate large numbers of people and that’s what they did in part by building lockdown prisons like ADX Florence in Colorado and countless others.

Anyone who got convicted in the 1990s and in the early 2000s and was labeled by the government as a “terrorist” automatically went into lockdown isolation units—we have seen this before at complexes like Abu Ghraib. There are also isolation medical units in the federal prison. Morerecently, COVID-19 protocol is that everyone gets put in utter isolation, whether that’s called an isolation unit or not. The goal to truly incapacitate thousands and thousands of people becomes really central to the mission of the BOP, and prisons at the state-level all fall in line with that. From the time that I was one of the first women in the Lexington HSU, the massification of control units has just become enormous. The 2011 and 2013 resistance out of Pelican Bay, as well as the strike in 2018 in South Carolina over conditions inside, are responses to this very deep, very serious commitment to the myth of rehabilitation that is imploding on itself.

There is no rehabilitation—there’s only suffering. The stories of people who survived those units are not the majority of people. The majority of people get destroyed by those units. The PIC has gone through major changes over the past several decades. Unfortunately, what we thought then has come to pass—if they could do it to this group of three, or five women for two years in a basement in Kentucky—then they’re going to do it every- where. And that is what happened.

Brown: The Lexington HSU was shut down in 1988, yet control units have continued to spread throughout the US. What limitations or politi- cal dangers are there in legislative organizing that we need to anticipate as best we can in our struggles against imprisonment? In other words, what advice or lessons would you share with abolitionist organizers today from the fight to close Lexington HSU?

Rosenberg: It’s important to make a division when doing “reform” vs abolition because abolition has a completely different meaning. Hav- ing been in prison myself and spending almost 17 years in federal prison and then seven years on parole after that, I came out of that experience being a completely committed abolitionist. And I got out before Are Prisons Obsolete? by Angela Davis was published. And when I did read that book I was like—yes, yes! At the same time, if we hadn’t had the vehicle of litigation to fight Lexington, we wouldn’t have had the plat- form to fight the overall unit.

There’s a dynamic there about what mechanisms exist that are systemic, that one may or may not have to use in order to have a way of fighting. Going on strike in a prison, a hunger strike in particular, is an incredible leap. And if you do make that leap, it’s almost impossible to come back from that. You’re complying when you return having either won some things or not won anything. Because really, everybody makes decisions when they’re inside. The question is—are they going to resist that day? Are they going to comply that day? Are you gonna have a fight about getting water that day? It’s ev- ery single thing. I realize that’s not exactly your question, but I think there is a dialectical relationship between the absolute imperative of abolition—of ending this system and all that entails—and having mechanisms and tactics that exist within any given struggle that you have to deploy in order to fight for both that specific goal and then the larger picture. In a lot of situations, they don’t have to be mutually exclusive.

“There is no rehabilitation—there’s only suffering. The stories of people who survived those units are not the majority of people. The majority of people get destroyed by those units. The PIC has gone through major changes over the past several decades. Unfortunately, what we thought then has come to pass—if they could do it to this group of three, or five women for two years in a basement in Kentucky—then they’re going to do it everywhere. And that is what happened.”

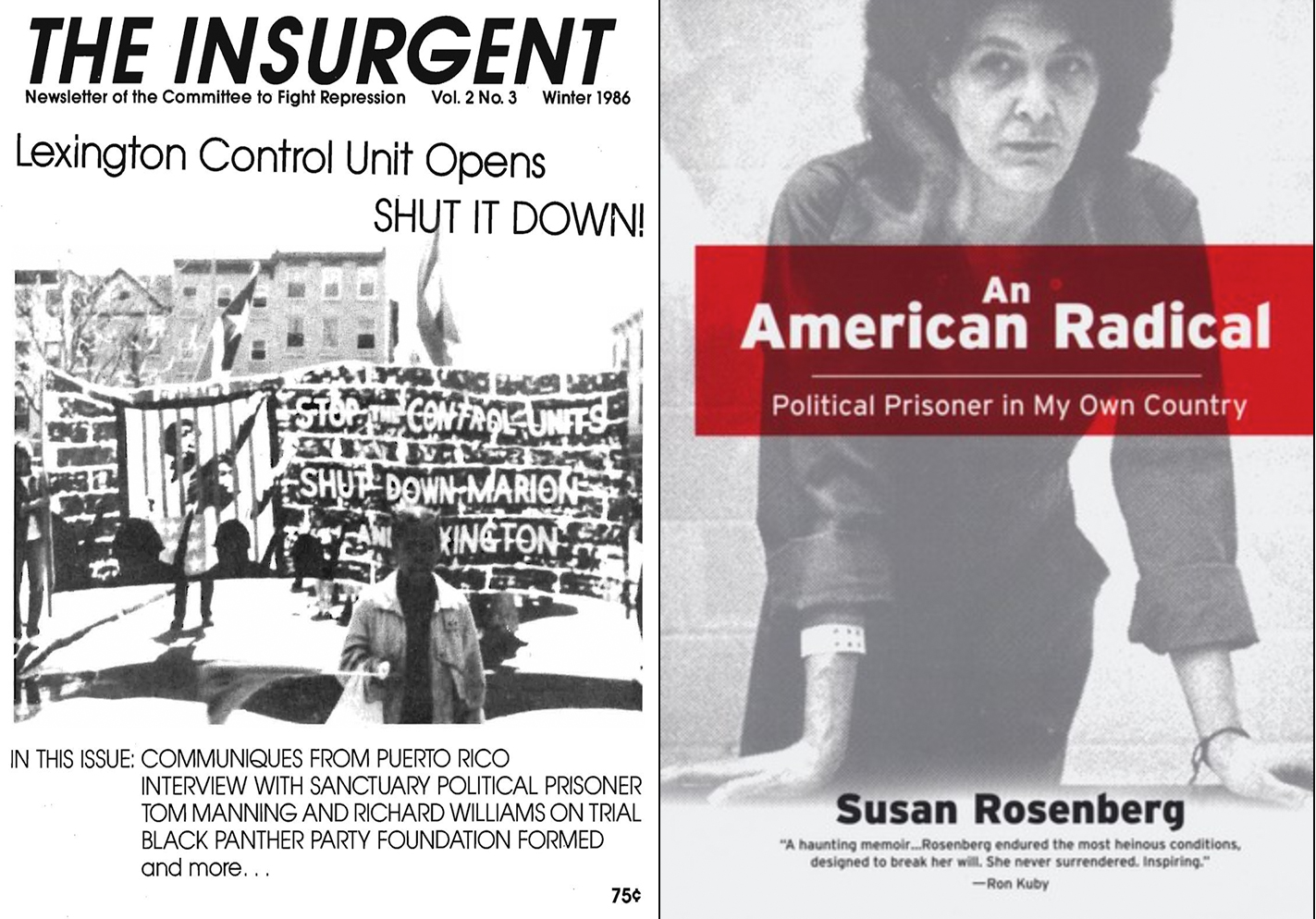

Left: A 1986 issue of the newsletter of the Committee to Fight Repression. Right: In 2011 Susan Rosenberg published An American Radical, about her time in the Lexington High Security Unit. Courtesy of Stephen Dillon, The Places Journal.

I have spent the last decade working on Dr. Mutulu Shakur’s case to get him out of prison. The goal was to get him out, which we did in December of 2022 before he passed away in July 2023. He died outside of prison, seven months after he was released. We were fighting an individual defense campaign and had to figure out the specific tactics and strategies to get him out without succumbing to the pressure and the resistance from the state. This meant utilizing every single possible thing—fighting for parole, fighting for clemency, mass organizing and getting 100,000 signatures, calling up the BOP and the Department of Justice and demanding his release, etc. If we hadn’t done those deep dives into their terrible system, we wouldn’t have been able to get him out.

Brown: I appreciate this response because what I’m hearing in your answer is the necessity of having a diversity of tactics and strategies with- in a given campaign to build power and achieve your goal. At Critical Resistance, we have a three-pronged campaign organizing approach that combines legislative and legal strategies, grassroots outreach and mobilization, and disciplined media and communications work to shift our terrain and “shrink and starve” the PIC, or chip away at the PIC’s power, resources, legitimacy, and scale over time. When we’re doing an anti-imprisonment or anti-policing campaign in coalition with other organizations, there will be a legal or legislative strategy, but it’s not the sole strategy being deployed. This is a good reminder of the importance of having a diversity of tactics in our organizing work, while remain- ing clear on our goal and the ultimate political horizon we are organizing towards.

Rosenberg: Yes, we have to bring in the ideological, systemic analysis into every level of our organizing work—what are the forces, who are they, and what are they doing? I hope there will come a time when we are much bigger, we have much more capacity, and when a mass struggle actually can impact in a real way making long- lasting change. Some of this is already happen- ing, but it must start with our understanding of our goal and what we are trying to achieve by fighting the system. This is not that new a problem for us—this is an issue for revolution and revolutionary organizing in every place.

Brown: Shifting to your own experience of imprisonment, what challenges did you face upon your release from Lexington HSU as a former political prisoner who experienced the worst of the worst prison conditions designed to de- stroy a revolutionary spirit and a commitment to revolutionary organizing?

Rosenberg: After the BOP closed Lexington, they immediately opened the first maximum security women’s prison, and that’s where I went right after Lexington. They had FCI Alderson, which was considered “max”, but looked like a farm, it was a different prison environment. There were 100 people in total isolation instead of three, so already we were seeing how they were expanding their own strategy even after we won the closure of Lexington at that point. They were committed to building these types of prisons for women. I was there for three years, and then after that I went to general population. What happened at Lexington didn’t ever go away. I remember Lexington very well to this day over 25 years later. The communities that I built and the relationships I had with other women in prison helped me. They became my best friends and helped me through the very worst of the aftermath of those psychological issues that I experienced at Lexington.

When we were at Lexington, people on the out- side would say, “Stop the torture! Stop the torture!” And we all said, it’s not torture. For us, this idea about psychological torture was not something that we really understood, even though we knew they were playing terrible mental games with us. For our own kind of self-worth, we didn’t want to admit that we were being tortured—but we were. They were torturing us. And when I got out, I recognized that’s actually what had happened—and was happening in other places in other ways for a long time.

“For our own kind of self-worth, we didn’t want to admit that we were being tortured—but we were. They were torturing us. And when I got out, I recognized that’s actually what had happened—and was happening in other places in other ways for a long time.”

Once I got out I decided that I would go to a psy- chological torture clinic, so I went to the NYU Program for Survivors of Torture. I wanted to go to a place where whether they agreed with my self-identity as a political prisoner or not, they would understand the experiences I had as torture. I wouldn’t have to beg a therapist to agree with me that I was a political person or ac- knowledge what the government did to me. I went into a whole therapeutic experience to try and deal with what had happened to me at Lexington during all those years of extreme imprisonment—and that made a huge difference. I feel like for anybody who’s inside you really need to have help when you get out. It’s not because of “recidivism”; it’s because of your humanity, and how to work through what this whole experience has been.

The other thing is that one doesn’t realize how deeply isolated one is when they’re inside. You try to keep being alive by being in some kind of environment that isn’t 100% hostile. When I got out the movement was there,but it was in a com- pletely different place than when I had gone in, and I realized how deeply isolated we were in- side. It had become very much non-profit and everybody had become a “professional”. The community here made me a part of them and that really, really made a difference.

The last thing I would say is I really recognize the divisions that exist because of privilege. I was white, I came from a fairly middle-class family, and my parents built a community to support me and a lot of other political prison- ers. They really went all the way out to try and help me recover. I didn’t come out and not have a place to live. I even got a masters inside when I was in general population. I could not have done that without access to resources outside.

Brown: You’ve been organizing against imperialism and oppression since the last era at least in the US when many people thought revolution was near. You were targeted as part of the counter-insurgency that the PIC emerged to wage against people making demands for change. Considering how you’ve continued to engage in political struggle and organize decades later, how have you seen our movements shift? Are you hopeful for lasting change? What do you think it would take given what you know from our movements past and now, to build a strong enough movement that can truly contend with the PIC and abolish its tools, including particularly vicious ones like control units?

Rosenberg: It feels like COINTELPRO again to me. It feels like that period, only now—where conditions are really different. I do believe that we are seeing more and more war-like activity by the right wing. This is compelling us to think about what we can do to respond—and that is a huge challenge that we’re all facing and are go- ing to face more and more.

I don’t want to live in a world where this is what the norm is. I think many people don’t want to live in a world like that. It’s incumbent on us who have a view of what kind of a world we wish we could have—need to have—to keep doing the work. That’s part of why I’m a teacher, it’s a platform and a mechanism by which I can put ideas in the world to people who live the experience of all of this repression, but might not and don’t necessarily have the analytical tools to make sense of it. It doesn’t make it acceptable, but once you have those tools you can make a decision about what to do or not to do about it. The summer of 2020 were the largest demonstrations ever in American history against white supremacy and the police. The state recognized this, and that’s part of what we are seeing now with this incredible right-wing, white supremacist, pro-imperialist, capitalist response by Democrats and Republicans and what they’re push- ing for our society. We have to fight that.

I’m not as optimistic as I was when I thought we were going to have a revolution in 10 years, but I do believe that there is a thread—a red thread— a group underneath that’s always going to keep fighting. I hope I’m going to be in that group until I’m not around anymore. There are thou- sands of people who will be, as well. If we want to make the kind of changes that abolition articu- lates so brilliantly, then we’re going to have to keep fighting. Keep fighting,struggling,organiz- ing, and all of those things. Has the movement changed? Yeah, and for the better in some ways even though it’s not as globally connected as we once were and anti-imperialism has somewhat of a different meaning now. I think the intersec- tionality that has evolved over the last 20 years around Black women’s leadership in particular and issues of misogyny, white supremacy, and the real clear linking of those in our understand- ingandhowtodealwiththemisahugeadvance. I don’t think it can be undervalued how impor- tant that is. So that makes me very optimistic.

Author Bio: Susan Rosenberg is a human rights and prisoners’ rights advocate, adjunct lecturer, award- winning writer, speaker, abolitionist, and a former US political prisoner. Currently she is an adjunct lecturer at Hunter College.