Ashanti Alston and Masai Ehehosi with Molly Porzig

From The Abolitionist No. 18: Surveillance

Editors Note: In exploring the role of surveillance as a cornerstone of the prison industrial complex (PIC), The Abolitionist wanted to examine it through its history, how it has been used and continues to repress struggles for liberation and self-determination. We interviewed two long-time revolutionaries and Critical Resistance members, Ashanti Alston and Masai Ehehosi, to outline some of this history as well as their own experiences organizing under surveillance during for more than 40 years.

A lot of people have very different definitions of surveillance. Can you explain what surveillance means to you?

Ashanti: It’s really important that people have a historical understanding. We have to always deal with what surveillance meant when there was this European conquest of the African continent–capturing and enslaving millions of Africans over to what became the United States; setting up slave ports and always having to have people keep an eye on those you’ve captured and on possible opposition to your quest to conquer the world. The whole system of slavery is one that is constant surveillance, as it is part of the mechanisms of conquest. When have colonized people not been under surveillance?

It’s important to understand what that means for those of us who are still victims of that original surveillance that came with the conquest of our people that we still have not been able to get off our backs yet in 2012.

Masai: That relates to how I see surveillance–it’s continuous. Years ago when Ashanti and I first started working together, we started to be surveilled and have been ever since. One of the definitions of surveillance is the continued observation of a person or group, especially if they are from one perspective doing something “illegal”. Revolution is always illegal to the oppressor since the independence struggle began. Independence is always considered illegal; just struggling for a just society is always illegal to the oppressor. If we’re talking about anything to cause real change, then we’re also talking about surveillance.

How has surveillance changed over time? What tactics have been used, how have they developed and how are they used now?

Masai: There’s always a greater use of technology to evolve more serious surveillance as time goes on and more advancements are invented. A lot of people who are targets or potential targets help a lot more now with surveillance than before, in the sense of smart phones, Facebook, [credit] cards and things that we do every day and we just don’t think about as surveillance. It may not be a thing where someone is visually seeing us, but our movements, actions and choices are being tracked. We contribute to it. We just don’t think there’s any other way.

When I used to work for the health department as a Communal Disease Control Investigator, we would ask people questions about their relationships, their lives, lots of private things. This was over 20 years ago and even back then a lot of people didn’t really realize what was going on. They would just give up information–about who partners were, gave network information and so on. Some the government already had, but a lot they didn’t. They then could make links of people based on information one person gave.

In terms of technology like cameras, some of those things that we got now couldn’t have even been done openly twenty years ago, because people would challenge it, but now people are accepting it. It comes back to the level of organizing that people are actually doing, because obviously a lot of the time people don’t actually feel safe, so they rely on the system’s tools either directly or indirectly. Some of us aren’t doing the organizing that we should be doing in the community that will actually make people feel and be safe. There’s a reason why they don’t feel safe—they’re buying into the propaganda, and we’re supposed to counteract that.

Ashanti: Technology is doing a hell of job, and those of us who want to challenge it have to think of how to do this differently. There’s an evolution of these agencies of conquest, but I keep focus on the role of the police, government, agencies, government programs, non-profit organizations, religious institutions, neighbors, business, media—all of these things are here to surveil or to create the conditions whereby the people that rule this country can keep the people under control, abiding by the law or rule. In some ways, things have changed drastically and in other ways not, because the key groups of people are still under this specific surveillance. This system does what it’s supposed to do to maintain white supremacy. I want people not to be naïve in what we face when we say we want to change this world. This reality and the history behind it, calls for abolition, not reform.

One example is a young activist brother in Cleveland, Ohio, saw them cameras up in the neighborhood and he also knew people in the neighborhood were calling for cameras because of the level of crime. He was trying to explain to everyone what those cameras really meant, but it fell on deaf ears. So he took it upon himself to actually start knocking them cameras out, regardless of what people thought. After so many generations of conquest, even those most impacted by the system begin to call for their own surveillance, repression. This tells you what the new challenge for those of us who say they want change. How do we get people to see that some of the very things that they’re asking for from government are not in their best interest?

How have you seen the surveillance of particular communities shift or intensify over time, specifically in terms of surveillance of immigrant communities, Muslim communities and young people?

Ashanti: I’m from Plainfield, New Jersey, and Plainfield’s a small town. It has a small police force, which may have contributed to the rebellion there in the’60’s, when Black folks were able to get weapons and run the police out. It wasn’t a magical thing, it was just doable and it was done.

In the mid 70’s to mid-80’s when I go to prison and came out, there was a large increase in the numbers, sophistication, as well as the resources that the police departments have access to in terms of technology, weaponry, and military training. Police forces were recruiting soldiers involved in imperialist wars to become police officers. That was a big change for me to see.

Things were so different from before we were captured and imprisoned, but we still came out with that same can do attitude. I don’t care how large the police get. I don’t care how terrified my people get. We have got to figure out how to get people to say, “No! We do not accept this occupation army!” I know we haven’t figured it out yet. But the idea is still valid that we must be self-determining and nothing should stop us from being that. We are up against a consciousness in our communities that really has been convinced that we cannot win, we must accommodate.

Masai: I agree we can do it, and I think sometimes folks don’t really want to acknowledge surveillance, so long as they’re struggling for certain things and it’s going to happen. I think they tend to gloss over it. For those who consider themselves to be leadership or politically aware, I think there’s an obligation to study what has happened and what is happening.

I come from the New Afrikan community, so what I see happening now is nothing new. It’s what I would have expected. People often assume when talking about the Muslim community that we’re talking about this whole different category of people or region of the world–of what we call the Middle East–and we sometimes forget a large number of Muslims actually are indigenous. If in fact we as Muslims are doing what we’re supposed to be doing, that is struggling against oppression, being heavily surveilled comes with it.

In the Muslim community, some folks speak in opposition of policies of the U.S. government and face serious charges and disappearance. People haven’t said anything other than what they felt. The U.S. government doesn’t really make an attempt to come up with any evidence or anything. In many cases the U.S. government agents in fact initiate the plots, provide equipment, and when folks voice opposition, they’re hit. It has had a way of making those folks in those communities skeptical of saying anything.

Ashanti: When I was living in New York, very conscious South Asians that were dealing with a lot of immigration issues were being picked up and kidnapped to so-called detentions. All of this caused intense powerlessness in terms of being able to stop government agencies in coming and just snatching them up. The state used all kinds of flimsy pretenses. Even some of them have been in the United States for decades. That pushed us to confront the issues that were going on in immigrant communities.

After 9/11, in Brooklyn, folks of color–Black and Latino–were attacking who they thought were Muslim. The Desi community got involved and they contacted Critical Resistance (CR) and Liberation Action Network out of Hunter College, asking for our help. It made us confront repression of oppressed people acted out on other oppressed communities, as well as the many different oppressions that happen within the same communities. Muslim communities and immigrant communities are so vulnerable especially because in many ways they’re being scapegoated for so many things. If you are their comrades, you got to figure out how to be in mutual solidarity, if possible providing protection from the government and corporations and from ignorance within oppressed communities acted out in pathological patriotism towards other people deemed to be different or the new enemy.

Can you talk about the NYPD surveillance of CR in relation to a document was released earlier this spring that revealed some surveillance the NYPD has been doing around the U.S.?

Ashanti: CR was very active, doing a lot of really concrete grassroots work and trying to raise this consciousness around the need to get rid of prisons, to get people really thinking about abolition and how it could be meaningful for them. As we had an office [in Brooklyn] and we were doing programs out of there, we noticed certain individuals started to get harassed more. We’ve always assumed the phone was getting tapped. It really came to a head when some of us went to the first Anarchists of Color Conference in Detroit. Coming back, we wanted to raise some money to help pay for some the costs. The police used that fundraising activity to vamp on us. They used the excuse that someone reported a minor drinking alcohol on the sidewalk. The next thing you know, asmall army of police are bursting in through the door, and there’s chaos. They ended up arresting a bunch of people. We knew the reason was because CR was building a foundation in the community and was helping to coalesce other organizations around this idea we do not need prisons. It didn’t look good for the police to just let this go, so somebody gave the order for them to shut us down.

CR made it through and was able to be stronger. A reason why we survived was because people came to each other’s aid–from protecting each other during the assault and getting pepper spray out of people’s faces, to taking care of people’s emotional trauma, to the work of jail support and getting the message out. CR broadened its work. People from many different organizations and communities were coming to the office to help. In a sense it’s like what Mao said: when your enemy attacks you, you must be doing something well. Things were coming together, because we knew concrete programs or ideas had to be the things that we organized around and not all the abstract stuff.

How has surveillance (or the fear of it) shifted the culture or practice of organizations and how has that impacted the work?

Ashanti: I want people to understand that as they are getting this from two individuals who have been doing this work for like 40 years or more, and we ain’t won yet. In the last 10 to 15 years, young folks know more than what we knew. They read more. More information is available. What I see is that they’re still or even more afraid to take risks when it comes to action whether its organizing or even doing those activities that require secrecy. People are looking at the consequences and they’re not taking the strategic risks. They’re doing actions and organizing in the kind of activism that is safe. I see it within organizations I’ve been a part of and it saddens me, knowing how bright these younger generations are and how energetic, but how they limit themselves in terms of so much they can do but it takes risks.

I know folks want to be as free and happy as we do. But if you cannot accept the system is going to come down on you, that very knowledge keeps you within a certain confine of what you do, and we’re going to keep perpetuating. How can you be free if you just do safe stuff? No matter how much people want to glorify the ‘60’s, especially the Panthers, people will not take them other steps to entrench themselves in the kind of organizing we did and begin to move on other extralegal organizing we had to do for our very survival. Therefore, a lot hasn’t changed in 40 years. Some good signs come up, but once the first group of people gets arrested or hurt, we’re back to nothing happening. We can still win if we prepare and take risks.

Masai: I know there’s a lot of fear amongst folks, but I don’t think it’s necessarily among the young, and it’s not just fear holding us back. I think, especially among younger folks now, people think it’s a legal struggle and that holding demonstrations will change things. Even the masses at these demonstrations that get a little unruly—I can relate to them, but as far as organizing and doing the things that need to be done, I just don’t know if they know what’s really necessary. The prisons are filling up. We have more control units now than ever and the folks in them ain’t even being heard out here. To think we can just keep petitioning is bullshit to me.

For example,enough of us out here don’t know the role gang units or gang related charges play on the inside. Not only is it hard for certain reasons to organize due to the guards and whatever, but also organizing itself is deemed a gang related activity. When prisoners do attempt to organize they’re thrown into the gang units. How those units work is in order to get certain things that you may need or to be released into general population in the prison, you have to name somebody as part of gang. I know CR has played a major role in supporting the hunger strikes that came out of Pelican Bay in California, running the media team, connecting with prisoners and family members and what not. I did similar work connecting with folks in these units when I worked at American Friends Service Committee, so I know a major challenge is struggling through the prisons control over communication and letters being used with surveillance to put more people in the gang units and to stop the organizing. We know from these situations that it’s about organizing, that’s all gang activity really means. It’s not about things being negative it’s about what poses a threat to the system.

What lessons have you learned that you think could strengthen the work that is happening now and that needs to happen?

Ashanti: As somebody who’s come out of CR, I understand abolition to require knowing the weapons they used to capture Africans have evolved today—the same shackles; those slave forts became prisons, and those same armed forces are there to control people so American life can keep on going. You’ve got to raise all issues that made this empire possible. We need to acknowledge our differences while being willing to do whatever is necessary to bring the monsters of imperialism down, whether we are Panthers, Zapatistas, struggling in other parts of the world, even the Arab countries. We cannot just confine to nonviolence as if we’re not trying to take anyone down. For those of us at the bottom, we’re watching the physical and spiritual devastation of our people every day.

Understanding the prison industrial complex, we’re not only dealing with something that includes the physical structure of prisons but also what that imprisonment really does– imprisoning our entire communities. Every agency in our communities uses surveillance whether you’re going for a job, going to the hospital, for a place to live, or you need funding. These are the hard truths we have to accept if we seriously want to change the world. When we accept this, we see we can actually bring this thing on. One of these generations we’re going to actually be free.We’re here. Masai, myself, Kai Lumumba Barrow–we’re here, so this is intergenerational. Everything that we have learned we are making available with the hope that kind of intergenerational collaboration continues.

Masai: When people get involved with PIC abolition, if they’re serious about their involvement, I don’t need to tell them certain things to do. If they’re serious about it, they’re going to run up into it. Back in the ‘70’s with the [Black Panther] Party, radicalizing folks wasn’t the words of the Party or other organizations, but it was participating in the programs in the community. Our work had an effect on them, so when the police started to shut down the breakfast programs and other programs, the community came out. They didn’t immediately rise up all the time, but they came out and they saw and understood why it was happening. I didn’t need to explain who are enemy was.

People need to read up on things like COINTELPRO and they need to do the work. If people have studied their history, and you are serious about this, then you know back in the day we were very serious about all this and still are. I know it was called being underground but I used to think of it as being above ground. We weren’t talking about supporting prisoners we were talking about liberating prisoners. Ashanti and I spent time and we actually left a lot of folks behind. When we were inside, folks inside were being politicized and we were working in there. The revolution didn’t stop for us. People were being trained to go back outside. We got out and it was like the revolution had stopped.

Is there anything else you want our readers to know?

Ashanti: I know it’s harder inside, and it’s gotten harder. Prisoners today are dealing with a different phenomenon. The prison administration created madness inside the prisons by manufacturing the growth of prison gangs, the flux of drugs, etc. That consciousness that was there during the revolutionary prison movement with George Jackson–that’s not there anymore, but there are individuals inside doing that Malcolm X transformation. They are trying to find themselves and be relevant, but they don’t get the support. A lot of people don’t know about them. I think those inside that are moving that way are getting the consciousness that they can play role, and they should continue to do that. Folks on the outside should figure out ways to support them, because some of them want to be a part of something that’s giving their life new meaning. So can we send them money, hook them up with other resources, go visit or get a lawyer on to help get them out? We on the outside got to keep finding ways to reach and connect with them. Prison is a microcosm of what we got out here, and there are definitely street organizations out here that we have a hard time reaching. That challenge can’t stop us. We got to brainstorm; we got to be creative.

For those in Pelican Bay and beyond in every prison: keep writing, learning, bonding with each other, and trying to create those revolutionary spaces you can use to survive and grow. Hopefully at some point we can begin to connect these struggles again like in the late ‘60’s and early ’70’s when the revolutionary prison movement and movement on the streets were solidly connected. We have to work towards that again.

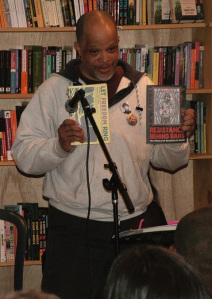

Ashanti Alston is a former member of the Black Panther Party and soldier in the Black Liberation Army, for which he was a political prisoner and prisoner of war for a total of 14 years. Since that time he’s been working with political prisoners building revolutionary movements mostly in the New York area. He has been a member of Critical Resistance and was CR’s Northeast Regional Coordinator. He has also been a part of The Institute for Anarchist Studies, Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, Student Liberation Action Movement and Anarchist People of Color.

Masai Ehehosi also a former prisoner of war both as a member of the Black Liberation Army and as a citizen of the Republic of New Afrika. First and foremost, he is a Muslim now. Masai is a founding and current member of Critical Resistance.

Molly Porzig is a member of Critical Resistance, Oakland, and is an editor for The Abolitionist.

Subscribe to The Abolitionist to get more content like this, and help us continue to send thousands of free subscriptions to people inside prison.