Peek inside Issue 38 of Critical Resistance’s The Abolitionist newspaper with this early release article by Mujeres de Frente on feminist unionism and collective organizing in Ecuador before, during, and after the Indigenous-led national strike of June 2022.

Focused on labor struggles & PIC abolition, Issue 38 is packed full of timely and useful analysis, reflection and resources for organizing inside and outside of cages, including articles on decriminalizing sex work, recent general strikes in Ecuador and Colombia, challenging the 13th Amendment and prison labor, and more. Support the project and subscribe to receive your copy hot off the press each issue!

Making A Living: Building New Worlds Against Punitivism and the State

by Mujeres de Frente

Editors’ Note: In this piece, Mujeres de Frente (Women Up Front) from Quito, Ecuador talk about their vision of abolition as an anti-punitive feminism focused primarily on the labor of “social reproduction.” The term “social reproduction” is used to describe work that is required to sustain life and has been systemically invisibilized, feminized, racialized, and, as explained in more in detail in the piece, hyper-criminalized. Mujeres de Frente organizers discuss the broader labor movement in relation to precarious feminized labor, the building of new social relations outside of capitalism, and reflections on their participation in the massive and successful National Strikes of 2022. We hope readers engage and struggle with the thoughts and examples of these visionary comrades.

Popular and Community Feminism: Against State and Prison Punitivism

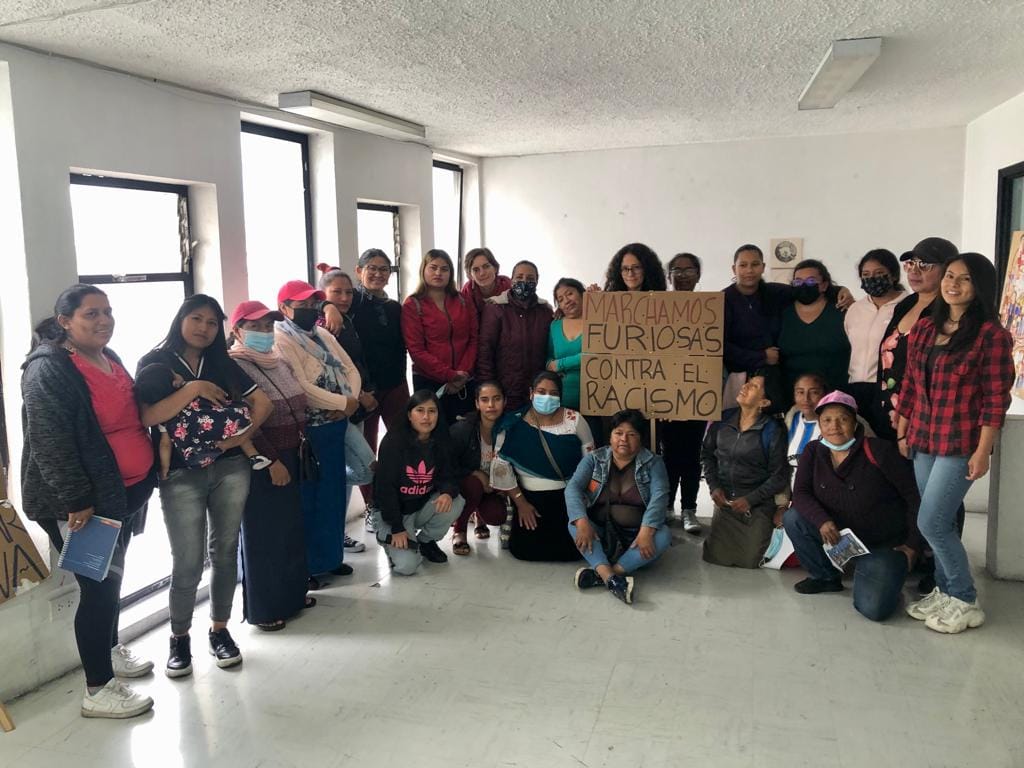

Mujeres de Frente (Women Up Front) was born in 2004 inside the women’s prison in Quito, Ecuador as a collective of imprisoned and non-imprisoned women engaged in a process of feminist research and action against the prison industrial complex (PIC). Today, we are a community of cooperation and care involving autonomous street sellers, recyclers, domestic workers, university students, professors, artists, formerly convicted women, family members of imprisoned people, boys, girls, and teenagers. We are indigenous, Afro-descendants, mestizas, whitened cholas, and sexually diverse people. Ours is a feminist organization against punishment. We build community based on reflection, production, and care anywhere that the social fabric is being continuously torn apart by the dynamics of capital accumulation and the prison state.

In the historic center of the city, we support La Casa de las Mujeres, a counter-cultural center open to various organizations and groups in the city. The meeting place for the School of Feminist and Popular Political Formation, the Wawas (Children) Space, the shared kitchen and dining rooms, a space for workshops and meetings, our Sewing Workshop, and the food basket and Catering of Mujeres de Frente, it is our space of transit, encounter and reunion, where processes of circulation of knowledge, legal support, co-investigation and daily accompaniment take place in every day. In the women’s section of the prison in the central-northern highlands region of the country, we also have our School of Feminist and Popular Political Formation and a space for the relatives of people imprisoned there.

Our collective work has allowed us to understand that labor struggles are not restricted to mere job- seeking. We who have been expelled from the formal economy and wage-labor relations stand as part of the (wrongly-defined) “informal” proletariat, whose presence is commonplace in the region. From there, we may say that our struggle is about seeking a dignified life among the interstices of the cities, jumping from legal and illegal, legitimate and illegitimate economies.

Therefore, our struggle is against the state, a state that impoverishes and criminalizes us and takes away our opportunities because of our class, race, and gender. The very state that prevents us from accessing dignified jobs and dignified lives is also the state that pushes us in one way or another to resort to subsistence economies through autonomous work, which is often not enough to provide for our families. It is the kind of work that is always being targeted and criminalized and also leads to job insecurity, preventing us from reproducing life with dignity and pushing us to the limits between what is legal and illegal. It is precisely the state that, through its bodies of control and repression like policing and other state actions, targets and prevents autonomous vendors from working. This system is not designed for us, and it turns all of our efforts to keep our jobs into a tedious and bureaucratic process, making it difficult for people who work in the informal economy to gain access to regularization or legalization of their situation.

Organizing during the National Strike of June 2022

The National Strike of June 2022 was called by the Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador (CONAIE—Indigenous Nationalities Confederation of Ecuador) and several Indigenous and social organizations against the government’s neoliberal policies, posing 10 concrete demands. For us, as an organization focused on the reconstruction of the community, it is important to recognize what it means to speak from the urban space, where the ties to community are constantly torn apart by the dynamics of corporate capitalism and the punitive state. At the same time, it is necessary to establish close bonds with the Indigenous-led organizations and communities that called for the National Strike. As daughters of the peoples displaced in the urban cities, our memory made us participate in the strike and recognize ourselves in a plural struggle. We believe that it is not necessary to be out in the country to see the needs we have every day—the hike in prices, the impossibility to access a home, the lack of food. This reality has pushed us to understand that this is not only the struggle of the Indigenous out there in the country but also the struggle of those who inhabit the city.

To us, it is essential to note that during our participation in the strike, we assumed the maintenance of the collection center, which allowed for the sustenance of the communities that spent the night in the university facility during the striking days. This work was required to sustain the material conditions of reproduction of the struggle. We stood as an assembly in the collection and distribution spaces to receive and distribute donations, with the aim of guaranteeing care during times of struggle. At the same time, we occupied positions as spokespersons, and several of our comrades took to the front lines so that we were not only at the rearguard of the strike, preoccupied with sustenance and care, but also at the forefront, exercising our political participation in the streets and other spaces.

It is worth noting that the strike also served to nurture alliances; the collection center was run through a collaborative effort between students and social movement activists, in particular with the participation of the transfeminist assembly. Sharing this experience allows us to recognize ourselves in diversity even more and overcome our own prejudices. These are individuals have lent a helping hand and taught us a lot; we are all people, and we should all raise our voices in this shared struggle, one that seeks the need to strengthen and acknowledge our demands and open the way to the varied struggles of different organizations. The capitalist, racist, and patriarchal state affects us all.

Addressing the relationship between labor, policing, imprisonment and state violence in Ecuador

To us, labor struggles are not only related to seeking formal jobs. Even though that is what classist sectors may say, and the left may keep as its hegemonic discourse, our struggle transcends toward “making a living” in contexts of dispossession and punishment. We believe that it is no coincidence that it is precisely us, who work in the streets, who suffer persecution, criminalization, and impoverishment on the part of the state. The informal proletariat has always had to adjust to the labor market’s aggressive dynamics, which are only considered for wealthier classes and social strata, and this prevents us from growing and sustaining just spaces of labor. Thus, through our understanding of the labor struggle as the comprehensive effort to realize social reproduction, we give meaning to an immediate relation in terms of struggle against punitivism. If most of the trades we engage in involve imprisonment, persecution, and criminalization—such as, for instance, the metropolitan police persecution of fellow female comrades working as autonomous vendors, so that, according to authorities, they are to a greater or lesser extent always violating the law—we may understand that there is a relation between the struggle for social reproduction and the struggle against punitivism, which is likewise a struggle against the state that punishes these forms of making a living.

This makes Mujeres de Frente an organization against jails, prisons, penal punishment, and, more generally, against the prison industrial complex. Through policing, penitentiary, and judicial officials, the system criminalizes the daily lives of women who seek social reproduction in the streets (between the legal and the illegal, the legitimate and illegitimate). For these reasons, our reading of labor struggle goes beyond seeking a job; rather, it relates to seeking life in adverse conditions.

The focus of the capitalist system is capital accumulation, and the labor movement seeks to maintain this monetary relation. We are interested in going beyond money. We are interested in being physically and emotionally well. We are interested in building relationships based on respect. We are not interested in working just because but rather realizing for ourselves the conditions of our existence: Who are we? Where do we come from? What is our history, our background?

To us, the aim of the struggle is not just to be able to work in order to be exploited but to build a new model beyond money, through which our labor and effort would center on all that is necessary to sustain life within our families and our communities. The idea is to do our work happily, because work would become an act of care and companionship, a collective endeavor, capable of building liberatory relationships and new possibilities. To us, fighting for work means respecting our value before the state, building communities that resist racism, criminalization, and poverty, creating tools that allow us to have our own voice and live in dignity, all led and by those who suffer day in and day out. Our struggle is comprehensive and represents an attempt to stand out as a collective and sustain ourselves and each other so that, despite seeking a salary or a job, we are likewise reflecting upon the logics we want to leave behind. This means considering the needs of our fellow female comrades, organizing in assemblies and by consensus, and working together as we sustain each other and the care of our space, which every day we are building with mutual aid.