By Nate Tan

This year has proven to be a uniquely dangerous year for Southeast Asian Americans facing deportation. On April 3, 2018 the largest deportation of Khmer Americans resulted in over 43 families being torn apart by the U.S. government. This was a deliberate message from the state to the Cambodian American community that it has no problem destroying the social fabric of Southeast Asian families. In the 1960s and 1970s, the U.S. military occupied, terrorized, and carpet bombed the sovereign nations of Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia. To date over 600 Cambodians have been deported back to Cambodia, over 16,000 have received deportation orders, and a total of 16,000 Southeast Asian refugees will be forced to leave the country. These deportations have largely remained hidden from the public eye, as many of these stories do not fit the “good immigrant” narrative that liberals can easily rally behind.

Many Southeast Asians—and Cambodian American refugees in particular—have deportation orders simply because they committed a “crime.” In this situation, the state relinquishes the refugee’s right to maintain residence in the U.S. They not only experience civil death like other imprisoned people but suffer complete removal from the country altogether. Because many find it difficult to advocate for the freedom of those who commit alleged crimes, a blind eye is turned on such individuals impacted by incarceration and deportation. But what if the conditions of our lives ask us to commit crimes? What if committing a crime was innate to our survival? How can we understand the conditions of poverty, refugee resettlement, and racism as a criminalization process? These questions inform the crucial argument that no one deserves to experience poverty, racism, refugee-ism or the violence of capitalism. As PIC abolitionists, we must demand the freedom of all criminalized people.

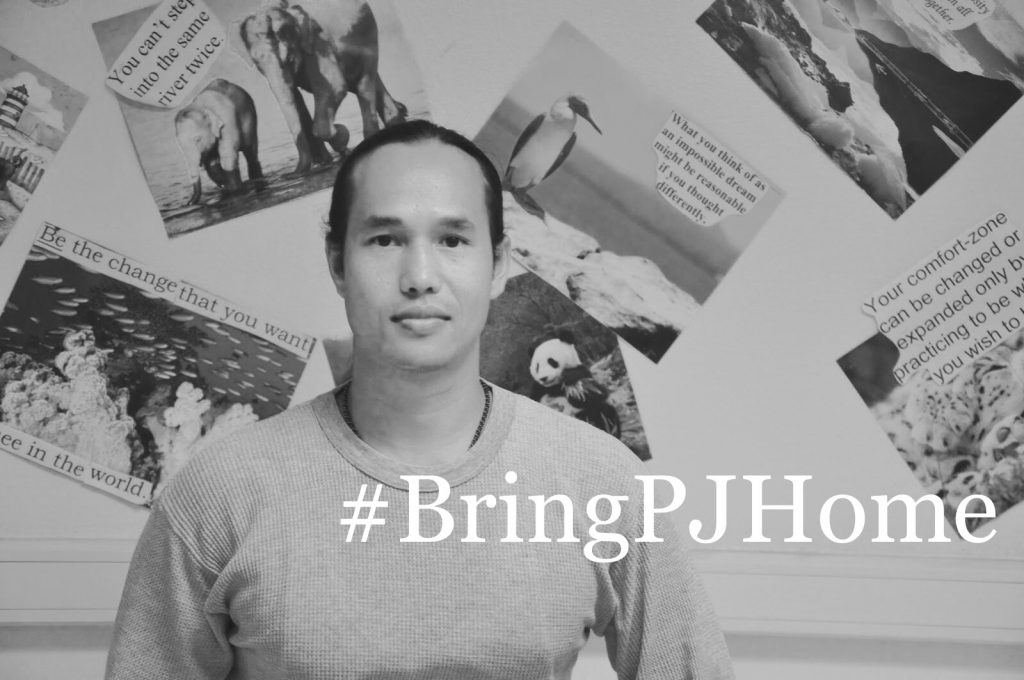

A case that highlights this type of abolitionist work is the #KeepPJHome campaign, an ongoing grassroots campaign that demands the freedom and unaltered stay of Borey “PJ” Ai. Importantly, this campaign does not only focus on PJ’s individual case but is organized with the larger goal of challenging incarceration and deportation more generally. The campaign first began as a project to free PJ from prison (#BringPJHome) and has since become the #KeepPJHome campaign, fighting against his deportation. Organizers in Asian Prisoner Support Committee (APSC) and I launched the #BringPJHome campaign in November of 2017. We were notified that ICE was going to launch a full fledged attack on the Southeast Asian community—specifically the Cambodian community—in what would be the largest ICE raid in Southeast Asian American history. Many of us volunteered in San Quentin State Prison and other California prisons and knew recent parolees that would be affected. PJ is a prisoner we worked with and love that recently paroled out who could potentially have been deported along with those picked up in these raids.

PJ was only 14 when he was incarcerated. He was sentenced to life at San Quentin State Prison and is notoriously known as one of the youngest prisoners to enter this adult facility. PJ is also a Cambodian refugee. He was born in a refugee camp and resettled in America in the mid 1980s as part of the U.S. Refugee Act to accept refugees from Southeast Asia. His family resettled in America after the U.S. bombings in Southeast Asia gave rise to the Khmer Rouge, a civil war that resulted in the genocide of a quarter of the Cambodian population. His resettlement to the United States as a refugee was riddled with challenges from the get-go. Like many refugees from Cambodia, PJ’s family did not speak English and suffered from the traumas of displacement and war. They resettled in Stockton, CA where the conditions of life were no better than the war-stricken country they escaped from.

At the time of PJ’s family resettlement, the U.S. was perfecting its own methods for subverting a wave of anti-racist and anti-war movements, which in part gave impetus to the prison industrial complex we know today. Between the late-1960s and 1980s, the U.S. began to criminalize and incarcerate people at exponential rates as a means to subdue mass uprising and maintain its imperialist control of the planet. PJ’s family resettled at a time where there was a hyper-militarization of police, cutbacks to social services, a “war on drugs,” a “war on poverty,” and the largest prison expansion project the world has ever seen. The circumstances that forced PJ’s family to resettle were the very same conditions that predetermined their fate, appearing always already as “criminal” in the white nation’s eye. Surviving extreme poverty, racism, and state terror became targeted criminal acts.

On January 17, 1989, Cleveland Elementary School, a school with predominantly Southeast Asian refugee children from Vietnam, and Cambodia, experienced a school yard shooting. The perpetrator was Patrick Edward Purdy, a white American citizen who is said to have held deep resentment toward Asian immigrants for “taking American jobs.” PJ was a student at Cleveland Elementary School when the shooting took place. PJ later recalled not wanting to go back to school and feeling unsafe after the shooting. It was in that feeling of unsafety that survival became essential for him. PJ joined a gang as a response to the violence in Stockton, which resulted in him committing a crime that landed him in prison at the age of 14. He became the youngest person to be sentenced to an adult prison in California history.

While imprisoned, PJ took the necessary steps to demonstrate “rehabilitation.” During his time in prison he completed his GED, became a state certified rape and crisis counselor and certified domestic violence counselor, and earned his Associate’s degree in Liberal Arts. In July 2016, after serving 20 years behind bars, PJ was granted parole on his first try. Immediately after his release, however, he was sent to an ICE detention center where he would wait for an order of deportation. He had become part of the many Cambodian individuals now at the mercy of the deportation machine.

We called in with PJ from ICE detention as other Asian American grassroots organizations demanded the deportations of Cambodian Americans come to an end. Other Asian American advocacy groups constantly called and contacted their representatives demanding that they stand up for PJ and the other folks impacted by incarceration and deportation. On the inside of ICE detention, while we were fighting for PJ’s freedom, PJ was working with the newly rounded up Cambodians in the ICE detention center he was being held at. He worked with other Cambodian Americans to re-open their cases and fight their deportation too. PJ encouraged other detainees to keep fighting and to keep their spirits up and made sure to connect people inside facing deportation with attorneys and resources that resulted in some of the detainees winning a stay here in the United States. PJ looked out for his community with unrelenting support as detainees inside and supporters outside were demanding the right to stay with their families in the United States. People involved with his campaign began to develop an abolitionist consciousness and framework that sought justice and liberation for all incarcerated and detained people.

Outside of ICE Detention walls, we, as #BringPJHome organizers, launched Pack the Court campaigns at all of his ICE hearings. We wrote letters to our district assembly members. We wrote letters to the Governor. We took “vacations” from work to advocate for PJ in Sacramento. We mobilized students from California colleges and universities. We mobilized with his family. We tried everything and anything that we believed would get PJ free. We love all the men we’ve worked with inside the prison system, and we love PJ. We were determined to stop his deportation because we knew if we could make the case that he didn’t deserve to be deported, then we could make the case that nobody should be deported. We launched #BringPJHome knowing it would be a long shot, but we were determined to fight for his freedom.

In talking about Southeast Asian detainees, PJ exemplifies the material conditions that lead so many to be incarcerated and then detained in ICE detention. He says: “Looking back now, big ‘ol influx of Southeast Asians coming to prison during the ‘80s. Why? Why so many all of a sudden, trauma passed on from generation to generation. We grew up in prison, most of us. We woke up, and find our way out of prison. Now we are sitting in ICE serving time again being separated from our families. So for me, what is most special thing is family. My whole life, just trying to find a family, trying to be a part of family.” PJ’s remarks demonstrate how the root of justice, liberation and consciousness lies something more—love. That in the pursuit of belonging and family is love, and it is love and struggle that will lead us to freedom. On May 10, 2018, after all the organizing, advocacy, and mobilizing, PJ was finally released from ICE detention. We were ecstatic. We didn’t know if it was due to our community organizing or if it was because ICE decided to release PJ on a whim, but we would take this as a win for us, for the community, and for PJ’s family. After 20 plus years of incarceration and then ICE detention, PJ finally took his first breath of freedom. After 20 plus years of seeing her son behind bars, on the weekend of Mother’s Day, PJ’s mom finally got to hold her son.

PJ is still “deportable” and we are still working to remove his deportation order. We as #BringPJHome organizers, now known as #KeepPJHome campaign organizers, are currently seeking a governor’s pardon as it is the only way to grant him a permanent stay here in the United States. His current status as an almost-free person (someone who is not currently incarcerated or in an ICE detention center) can be attributed to the organizers and advocates who saw that his freedom was a necessary step towards the freedom of all imprisoned people with deportation orders. This campaign was a pinnacle moment in the Cambodian American community and the anti-deportation movement at large. This campaign provided a framework and praxis that allowed us to work beyond the good immigrant and bad immigrant narrative, and shed light on the compounding effects of poverty, racism, and refugee resettlement. It proved to us, outside organizers, that in a perfect world without U.S. imperialism, poverty, and racism, we wouldn’t have to be fight for PJ. The conditions in his life would not have been set up for him to be criminal, if those systems of violence did not exist. We were determined to demonstrate that we can work towards the abolition of all those systems. PJ’s campaign exemplifies the necessity of fighting for all incarcerated and deportable people.

Nate Tan is an organizer with Asian Prisoner Support Committee and helped lead the#BringPJHome campaign.

Editor’s Note: On October 16, 2018, PJ received a recommendation for a governor’s pardon, achieving a crucial step towards his freedom.